During the formation of the Americas, certain histories, primarily Black and Brown narratives, were forcefully pushed to the side in order to center Eurocentric hegemonic culture. Within this framework, imperial narratives are often glorified and deemed the cultural norm; anything contrary to that is usually deemed as deviant or “other”. The ideals that stem from this oppressive society aim to erase and silence the voices and experiences of these individuals forcefully put in the margins. The long lasting effects of settler colonialism have allowed for imperialist histories to appear “indigenized”, and make the oppressors' recollection of history the “default.”(1) Seen with the United States’ occupation and later takeover of Indigenous Mexican land, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo became written proof of the Eurocentric power forcefully annexing land. It displaced thousands of individuals from their home country and strengthened the United States’ attempt to “nativize” themselves to land that was never truly theirs. (2) All the while, the historical genocide of Indigenous peoples and chattel slavery were precursors to the formations to an Eurocentric canon and culture. In Rewriting the Canon, the artists showcased recenter those “invisibilized” bodies and cultures and reaffirm their worthiness to belong and be seen.

While what we are told as ‘history’ can sometimes be thought of as fact, it is greatly influenced by who writes it. In the case of the United States, those who write the history are the members of the White ruling class; this perspective has had detrimental effects upon Black and Brown communities that have lived generations without their stories being told. Most importantly, these whitewashed accounts of history have a powerful legacy in our country today, and the dismissal of centuries of racism and mass genocide has contributed to the lack of acknowledgment and lack of action towards racial justice, in the past and present. In the pages below, the four artists chosen each provide different perspectives and approaches to rewriting Eurocentric history to include the experiences and accounts from marginalized communities.

While what we are told as ‘history’ can sometimes be thought of as fact, it is greatly influenced by who writes it. In the case of the United States, those who write the history are the members of the White ruling class; this perspective has had detrimental effects upon Black and Brown communities that have lived generations without their stories being told. Most importantly, these whitewashed accounts of history have a powerful legacy in our country today, and the dismissal of centuries of racism and mass genocide has contributed to the lack of acknowledgment and lack of action towards racial justice, in the past and present. In the pages below, the four artists chosen each provide different perspectives and approaches to rewriting Eurocentric history to include the experiences and accounts from marginalized communities.

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization, Indigeneity, and Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 12.

- Gloria E. Anzaldúa, “The Homeland, Aztlán,” Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 1-13.

The Birth of Oshun

David Fernandez

Born in Chicago in 1984 , Harmonia Rosales embeds her cultural roots in many of her paintings. A woman of Afro-Cuban descent, she invokes her heritage in her work by pulling from the African religion Ifá, but more specifically its successor, the Afro-Cuban religion Santería. The religious practice was formulated after enslaved Africans were forcefully brought over to the Americas and were required to suppress their own religion. In order to counteract this, the Africans merged their religion with Catholicism, and embedded their deities, the Orishas, into Catholic saints so they could still practice in secret. Thus, they created a syncretic religion in the Americas.

Within her series titled Black Imaginary to Counter Hegemony (B.I.T.C.H.), Rosales utilizes imagery of the Orisha in one of her paintings for the collection titled The Birth of Oshun. The captivating painting instantly relates to Sandro Botticelli’s work The Birth of Venus. In Botticelli’s rendition, we see Venus, the Goddess of Love and beauty, being born on the island of Cyprus out of the center of a scallop. To her left are the Greek wind deities Zephyr and Aura, blowing the sea foam that brought forth Venus’ birth. To her right stands one of the Graces or Hora of Spring who brings a flower patterned cloak to cover the newborn Goddess.(1) Venus stands in the middle of the frame, with porcelain white skin, and long flowing blonde hair, supposedly being the physical embodiment of femininity and beauty. Botticelli’s representation of Venus falls under the historical idea that Whiteness is a necessary precursor to be considered beautiful. (2)

In The Birth of Oshun, Rosales subverts Botticelli’s image and the oppressive hegemonic standards of beauty. In the center of the image, in place of the stereotypical Venus, is a dark-skinned Black woman. Her skin is speckled with patches of gold, which mimics the skin condition vitiligo and gives the woman an enchanting and regal quality to her. The woman in the middle is Oshun, the Yoruba Goddess of femininity, beauty and love. Rosales brings forth an Afro-diasporic deity that parallels the more widely known and accepted Greek Goddess. And much like Venus, Oshun is also coveted by her fellow Orishas. To the right of Oshun is Yemayá, the Goddess of the ocean and motherhood, taking the spot of the Horae in the original. Yemayá, the overseer of fertility, becomes the perfect counterpart for the Horae of Spring. Being the manifestation of spring, the Horae embodies the fruitfulness of the land, which aligns with the powers the ocean Goddess possesses. To the left is Obatalá, the androgynous creator of man and woman sweeping down with Oyá in their arms, the Orisha of whirlwinds. The two mimic the wind deities in the original painting. In Rosales' depiction, Oyá is now the one who brings forth the sea foam that would birth Venus, if this were the original; Obatalá’s presence in the composition highlights the story of how they breathed life into the people they created, and it looks like with the help of Oyá’s winds, the two are teaming up to birth Oshun. Countering Botticelli’s image, Rosales gives Oshun short coiled hair, disrupting the idea that long, flowing hair is a necessity for beauty. Rosales herself has said that the inclusion of Oshun’s vitiligo was to show that things that may be considered “imperfections” are also beautiful. (3)

Harmonia Rosales’ painting counteracts many of society's standards. Instead of looking towards the Greeks, which has historically been done for finding the ideals of anatomy and proportion, amongst other things, Rosales looks elsewhere. By invoking the Orishas within her work, she is able to make Black Indigenous beliefs her foundation. She shows that Afro-diasporic beliefs have a place within widespread culture and affirms that they should also be looked at for ideals. She positions the Black woman, and specifically a dark-skinned Black woman, as the pinnacle of beauty, uplifting an underrepresented group within this area. With her work, Rosales confronts society’s conditioning and affinity towards Eurocentric attributes and ruptures the historic positions Black individuals have been placed in in different forms of media, and in this case more specifically classical paintings. Rosales allows the viewer to see Black individuals represented in imagery that has been historically lauded over, demanding that this community also be afforded the praise and shows that Blackness is something that is beautifully divine.

David Fernandez

Born in Chicago in 1984 , Harmonia Rosales embeds her cultural roots in many of her paintings. A woman of Afro-Cuban descent, she invokes her heritage in her work by pulling from the African religion Ifá, but more specifically its successor, the Afro-Cuban religion Santería. The religious practice was formulated after enslaved Africans were forcefully brought over to the Americas and were required to suppress their own religion. In order to counteract this, the Africans merged their religion with Catholicism, and embedded their deities, the Orishas, into Catholic saints so they could still practice in secret. Thus, they created a syncretic religion in the Americas.

Within her series titled Black Imaginary to Counter Hegemony (B.I.T.C.H.), Rosales utilizes imagery of the Orisha in one of her paintings for the collection titled The Birth of Oshun. The captivating painting instantly relates to Sandro Botticelli’s work The Birth of Venus. In Botticelli’s rendition, we see Venus, the Goddess of Love and beauty, being born on the island of Cyprus out of the center of a scallop. To her left are the Greek wind deities Zephyr and Aura, blowing the sea foam that brought forth Venus’ birth. To her right stands one of the Graces or Hora of Spring who brings a flower patterned cloak to cover the newborn Goddess.(1) Venus stands in the middle of the frame, with porcelain white skin, and long flowing blonde hair, supposedly being the physical embodiment of femininity and beauty. Botticelli’s representation of Venus falls under the historical idea that Whiteness is a necessary precursor to be considered beautiful. (2)

In The Birth of Oshun, Rosales subverts Botticelli’s image and the oppressive hegemonic standards of beauty. In the center of the image, in place of the stereotypical Venus, is a dark-skinned Black woman. Her skin is speckled with patches of gold, which mimics the skin condition vitiligo and gives the woman an enchanting and regal quality to her. The woman in the middle is Oshun, the Yoruba Goddess of femininity, beauty and love. Rosales brings forth an Afro-diasporic deity that parallels the more widely known and accepted Greek Goddess. And much like Venus, Oshun is also coveted by her fellow Orishas. To the right of Oshun is Yemayá, the Goddess of the ocean and motherhood, taking the spot of the Horae in the original. Yemayá, the overseer of fertility, becomes the perfect counterpart for the Horae of Spring. Being the manifestation of spring, the Horae embodies the fruitfulness of the land, which aligns with the powers the ocean Goddess possesses. To the left is Obatalá, the androgynous creator of man and woman sweeping down with Oyá in their arms, the Orisha of whirlwinds. The two mimic the wind deities in the original painting. In Rosales' depiction, Oyá is now the one who brings forth the sea foam that would birth Venus, if this were the original; Obatalá’s presence in the composition highlights the story of how they breathed life into the people they created, and it looks like with the help of Oyá’s winds, the two are teaming up to birth Oshun. Countering Botticelli’s image, Rosales gives Oshun short coiled hair, disrupting the idea that long, flowing hair is a necessity for beauty. Rosales herself has said that the inclusion of Oshun’s vitiligo was to show that things that may be considered “imperfections” are also beautiful. (3)

Harmonia Rosales’ painting counteracts many of society's standards. Instead of looking towards the Greeks, which has historically been done for finding the ideals of anatomy and proportion, amongst other things, Rosales looks elsewhere. By invoking the Orishas within her work, she is able to make Black Indigenous beliefs her foundation. She shows that Afro-diasporic beliefs have a place within widespread culture and affirms that they should also be looked at for ideals. She positions the Black woman, and specifically a dark-skinned Black woman, as the pinnacle of beauty, uplifting an underrepresented group within this area. With her work, Rosales confronts society’s conditioning and affinity towards Eurocentric attributes and ruptures the historic positions Black individuals have been placed in in different forms of media, and in this case more specifically classical paintings. Rosales allows the viewer to see Black individuals represented in imagery that has been historically lauded over, demanding that this community also be afforded the praise and shows that Blackness is something that is beautifully divine.

- The Uffizi Gallery, “The Birth of Venus”, Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi, https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/birth-of-venus#:~:text=Known%20as%20the%20%E2%80%9CBirth%20of,as%20perfect%20as%20a%20pearl,. Accessed May 6th 2021.

- Leah Donnella, “Is Beauty in the Eyes of the Colonizer?," podcast audio, February 6, 2019, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2019/02/06/685506578/is-beauty-in-the-eyes-of-the-colonizer.

- Sonaiya Kelley, “Words and Pictures: viral artist Harmonia Rosales’ first collection of paintings reimagines classic works with black femininity”, September 21, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-cm-harmonia-rosales-the-creation-of-god-reimagined-20170919-story.html.

Christopher Gregory-Rivera, selections from In the Mouth of the Jaguar, 2018. © Christopher Gregory-Rivera.

In the Mouth of the Jaguar

Ethan Kuniholm

Black and Brown narratives have constantly been forced aside by the Eurocentric hegemony that is given center stage by mainstream media and educational institutions. As history is relative to those who wrote it, imperial narratives aim to silence the voices of the colonized. This causes many problems in the present. For example, by only consuming imperial narratives, it becomes easier for today’s generations to dismiss racism, mass-genocide, recognize problematic structures, and begin work to correct them. Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s photo series, "In the Mouth of the Jaguar," documents the current plight of the Guyanese people. Since 1594, when British colonizer Sir Walter Raleigh wrote, “Guiana is a country that hath yet her maidenhead, never been sacked, turned, nor wrought; ... The graves have not been opened for gold, the mines not broken ... It hath never been entered by any army of strength, and never conquered or possessed by any Christian prince,” many foreign powers have illegally extracted many resources from Guyana including diamonds, gold, and boxite. (1) Now, in 2021, a new resource has been discovered in Guyana: oil. With this discovery Guyana, one of the poorest countries in the world now finds itself in a unique position. A drilling operation off the coast of Guyana promises to bring in an annual amount of twenty billion dollars per year to a country of less than one million people. (2) However, will the trend of colonization, greed, and corruption prevail, leaving the everyday average Guyanese citizen in the same position as before, or will the narrative change? Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s projects are focused on the idea of rescuing historical narratives through documentary photography in order to promote a better

understanding of the present. His project, In The Mouth of The Jaguar, is no different. By examining the people of Guyana and what surrounds them he becomes a voice speaking out to the world delivering their story to a worldwide audience. Using this method he brings sidelined histories to the foreground best described in his own words from a podcast, “All these photographs become narratives that are something people can attach to and understand the effects of what’s going on.” (3) By capturing direct portraits of the Guyanese people who are being directly affected by Exxon-Mobil’s offshore oil drilling, he is appealing to viewer’s empathy. By doing this his work acts as a news article, relaying information of a struggle to a wider audience. However, where a news article falls short is its lack of representation and accounts of actual real people. Their faces, hearts, and possessions are what Christopher Gregory-Rivera captures, allowing the audience to experience the densely layered visual histories that sediments itself within each crevice and thread that makes up these portraits. This is why Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s photos are so powerful. They highlight historical narratives of Black and Brown people like the situation of the Guyanese and by doing this bring to light their situation and educate the public on stories which would otherwise be unheard.

Ethan Kuniholm

Black and Brown narratives have constantly been forced aside by the Eurocentric hegemony that is given center stage by mainstream media and educational institutions. As history is relative to those who wrote it, imperial narratives aim to silence the voices of the colonized. This causes many problems in the present. For example, by only consuming imperial narratives, it becomes easier for today’s generations to dismiss racism, mass-genocide, recognize problematic structures, and begin work to correct them. Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s photo series, "In the Mouth of the Jaguar," documents the current plight of the Guyanese people. Since 1594, when British colonizer Sir Walter Raleigh wrote, “Guiana is a country that hath yet her maidenhead, never been sacked, turned, nor wrought; ... The graves have not been opened for gold, the mines not broken ... It hath never been entered by any army of strength, and never conquered or possessed by any Christian prince,” many foreign powers have illegally extracted many resources from Guyana including diamonds, gold, and boxite. (1) Now, in 2021, a new resource has been discovered in Guyana: oil. With this discovery Guyana, one of the poorest countries in the world now finds itself in a unique position. A drilling operation off the coast of Guyana promises to bring in an annual amount of twenty billion dollars per year to a country of less than one million people. (2) However, will the trend of colonization, greed, and corruption prevail, leaving the everyday average Guyanese citizen in the same position as before, or will the narrative change? Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s projects are focused on the idea of rescuing historical narratives through documentary photography in order to promote a better

understanding of the present. His project, In The Mouth of The Jaguar, is no different. By examining the people of Guyana and what surrounds them he becomes a voice speaking out to the world delivering their story to a worldwide audience. Using this method he brings sidelined histories to the foreground best described in his own words from a podcast, “All these photographs become narratives that are something people can attach to and understand the effects of what’s going on.” (3) By capturing direct portraits of the Guyanese people who are being directly affected by Exxon-Mobil’s offshore oil drilling, he is appealing to viewer’s empathy. By doing this his work acts as a news article, relaying information of a struggle to a wider audience. However, where a news article falls short is its lack of representation and accounts of actual real people. Their faces, hearts, and possessions are what Christopher Gregory-Rivera captures, allowing the audience to experience the densely layered visual histories that sediments itself within each crevice and thread that makes up these portraits. This is why Christopher Gregory-Rivera’s photos are so powerful. They highlight historical narratives of Black and Brown people like the situation of the Guyanese and by doing this bring to light their situation and educate the public on stories which would otherwise be unheard.

- Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discovery of Guiana (1848 Gutenberg Press), 35.

- Christopher M. Matthews, "World’s Biggest New Oil Find Turns Guyana Upside Down," The Wall Street Journal, February 28, 2021.

- Reciprocity Podcast, "Christopher Gregory-Rivera - New York City and Puerto Rico Based Photographer," 2020 Brett Carlsen.

- Laura Aguilar, Nature Self Portrait #2, 1996, gelatin silver print, 14 x 19 `1/16 in. UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. © Laura Aguilar.

- Laura Aguilar, Laura, 1988, gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. © Laura Aguilar.

Nature Self-Portrait #2

Avery Shaw

Picture the American Southwestern landscape. What images come to mind? Vast open space, large and spacious sky, untouched terrain and ecosystem, empty of human connection and civilization. The portrait painted by the mainstream American culture of this land is an intentional one. The push to colonize required a concept of “uninhabited land.” It would be a different story if the land was illustrated with the human bodies that occupied it previous to colonization. Laura Aguilar’s silver gelatin print Nature Self Portrait #2 is a redefinition of the landscape by including a portrait of her own non-White body inhabiting the space that the White Western aesthetic has claimed as its own.

Laura Aguilar’s work “ruptures a colonial viewpoint,” as Macarena Gómez-Barris puts it. (1) By placing her non-white body in a landscape that has been ideologically owned by White men, Aguilar is reclaiming a land and redefining a conception of ownership. Through a single photograph, Aguilar is making multiple challenges to the mainstream cannon. Challenges to who the land belongs to, what a female nude looks like, what photography is made to capture.

Nature Self Portrait #2 is a part of a larger Nature Self-Portrait series. In the series, Aguilar took dozens of photographs in the El Malpais National Monument (Northwestern New Mexico), Gila National Forest (Southwestern New Mexico), and Mojave Desert (Southeastern California). The series cannot be understood without realizing the context of these locations. These locations are loaded with history of territorial feuds, aggressive US expansionism and destruction, native land defense. The Gila Mountains are a historical site of confrontation and bloodshed between Anglo colonists and the Indigenous Apache civilians. Aguilar refuses to show the landscape without her physical form in direct subject. It is a counter attack, and a declaration of indigenous bodies and history that have been purposefully subverted in through the Western canon. She is demanding that the viewer contemplates how the mixed-race body has been historically made invisible. As Gómez-Barris puts it, she “visually blocks the project of American expansionism.” (2)

But aside from location, the more initially jarring element of the photograph is the figure. It would be a lie to say Aguilar’s large body, naked and exposed, wasn’t the first thing you noticed in the piece. Art critic Laura Cottingham describes why Aguilar’s approach to her self-portrait feels different from what was normally depicted in photography at the time. She writes, “While earlier portrait photographers who have cast their eye on the diverse range of human physical appearances have often chosen, like Diane Arbus and Joel Peter-Witkin, to focus on the freakishness of their subjects, Aguilar naturalizes her subjects.” (3) Aguilar presents her body with complete respect, with complete peace. The visual similarities between her landscape surroundings and her body’s shape insinuate an appreciation and beauty of the forms and folds of her natural body, alike to the appreciation of earth’s natural landscape.

Aguilar herself was a large-bodied, working-class ,queer Chicana woman living in the US, and her work demanded understanding, appreciation, and respect for all levels of her identity. In another piece titled Laura, Aguilar writes, “I’m not comfortable with the word Lesbian, but as each day goes by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA. I know some people see me as very child-like, naive. Maybe so. I am. But I will be damned if I let this part of me die!” (4) While this statement contemplates her sexuality, she brings the same fervor, determination, and stubbornness to her entire body of work. Aguilar did not make sacrifices for everyone; she was on a journey to discover who she was, where was her “home,” and how she could help others by working through these questions herself.

Avery Shaw

Picture the American Southwestern landscape. What images come to mind? Vast open space, large and spacious sky, untouched terrain and ecosystem, empty of human connection and civilization. The portrait painted by the mainstream American culture of this land is an intentional one. The push to colonize required a concept of “uninhabited land.” It would be a different story if the land was illustrated with the human bodies that occupied it previous to colonization. Laura Aguilar’s silver gelatin print Nature Self Portrait #2 is a redefinition of the landscape by including a portrait of her own non-White body inhabiting the space that the White Western aesthetic has claimed as its own.

Laura Aguilar’s work “ruptures a colonial viewpoint,” as Macarena Gómez-Barris puts it. (1) By placing her non-white body in a landscape that has been ideologically owned by White men, Aguilar is reclaiming a land and redefining a conception of ownership. Through a single photograph, Aguilar is making multiple challenges to the mainstream cannon. Challenges to who the land belongs to, what a female nude looks like, what photography is made to capture.

Nature Self Portrait #2 is a part of a larger Nature Self-Portrait series. In the series, Aguilar took dozens of photographs in the El Malpais National Monument (Northwestern New Mexico), Gila National Forest (Southwestern New Mexico), and Mojave Desert (Southeastern California). The series cannot be understood without realizing the context of these locations. These locations are loaded with history of territorial feuds, aggressive US expansionism and destruction, native land defense. The Gila Mountains are a historical site of confrontation and bloodshed between Anglo colonists and the Indigenous Apache civilians. Aguilar refuses to show the landscape without her physical form in direct subject. It is a counter attack, and a declaration of indigenous bodies and history that have been purposefully subverted in through the Western canon. She is demanding that the viewer contemplates how the mixed-race body has been historically made invisible. As Gómez-Barris puts it, she “visually blocks the project of American expansionism.” (2)

But aside from location, the more initially jarring element of the photograph is the figure. It would be a lie to say Aguilar’s large body, naked and exposed, wasn’t the first thing you noticed in the piece. Art critic Laura Cottingham describes why Aguilar’s approach to her self-portrait feels different from what was normally depicted in photography at the time. She writes, “While earlier portrait photographers who have cast their eye on the diverse range of human physical appearances have often chosen, like Diane Arbus and Joel Peter-Witkin, to focus on the freakishness of their subjects, Aguilar naturalizes her subjects.” (3) Aguilar presents her body with complete respect, with complete peace. The visual similarities between her landscape surroundings and her body’s shape insinuate an appreciation and beauty of the forms and folds of her natural body, alike to the appreciation of earth’s natural landscape.

Aguilar herself was a large-bodied, working-class ,queer Chicana woman living in the US, and her work demanded understanding, appreciation, and respect for all levels of her identity. In another piece titled Laura, Aguilar writes, “I’m not comfortable with the word Lesbian, but as each day goes by I’m more and more comfortable with the word LAURA. I know some people see me as very child-like, naive. Maybe so. I am. But I will be damned if I let this part of me die!” (4) While this statement contemplates her sexuality, she brings the same fervor, determination, and stubbornness to her entire body of work. Aguilar did not make sacrifices for everyone; she was on a journey to discover who she was, where was her “home,” and how she could help others by working through these questions herself.

- Macarena Gómez-Barrs, "Mestiza Cultural Memory: The Self-Ecologies of Laura Aguilar," in Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, ed. Rebecca Epstein (Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2017), 79–85.

- Gómez-Barris, "Mestiza Cultural Memory," 79–85.

- Laura Cottingham, “Stillness; Summer 1999 International Artist-in-Residence Program," ArtSpace, www.artpace.org/works/iair/iair_summer_1999/stillness.

- Laura Aguilar, Laura, 1988, gelatin silver print from Latina Lesbians series.

Café

Adrienne Sarasy

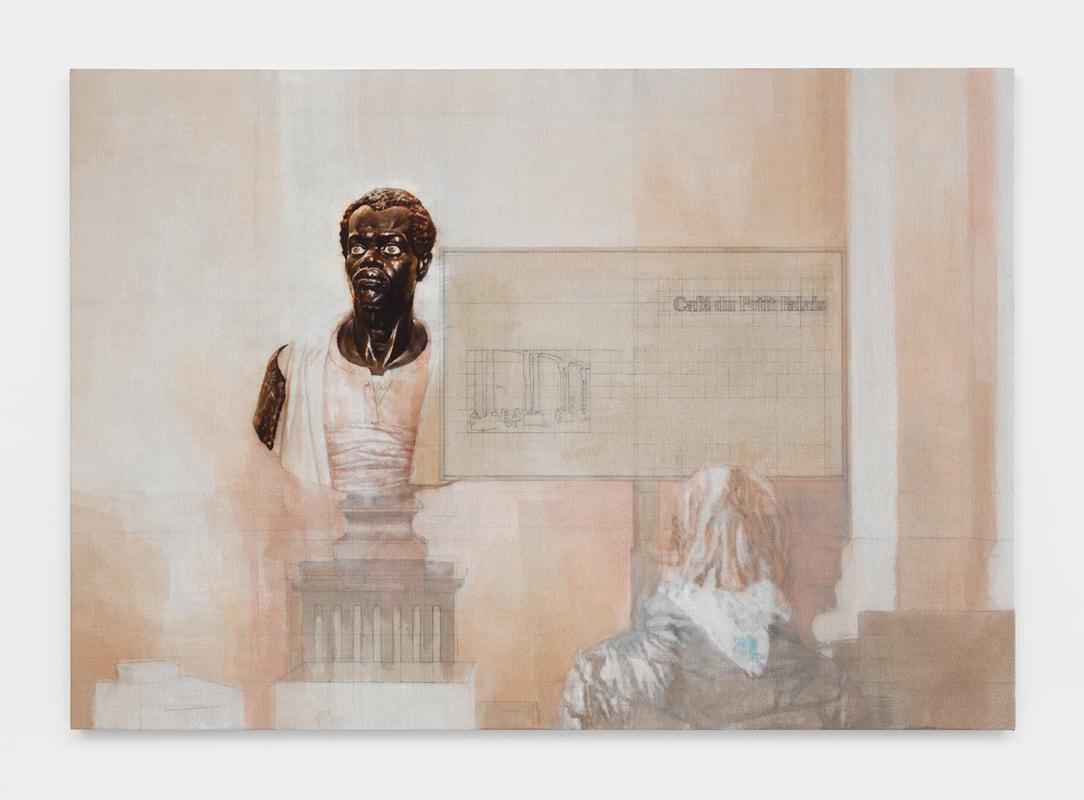

Esteban Jefferson’s Café (2020) is part of his recent exhibition Petit Palais, shown at Tanya Leighton, Berlin. The oil on linen work, presents itself in a state of being drafted, washes of muted pink and beige tones melting over blue and graphite colored lines, from which the composition’s forms emerge. There is a sensation of aged parchment rendered within the painting’s surface, bearing the gridded lines of an architectural blueprint or more pointedly, the residual line systems of high renaissance underpainting.

As a whole the composition depicts an encounter Jefferson had with an unattributed bust of an African figure during a visit to the Petit Palais in Paris. (1) Unlike the majority of the works of art in the Petit Palais, which are held in the numerous galleries and bear a tag indicating the works title, maker and provenance, this work is placed obscurely in a foyer next to which is a sign pointing visitors in the direction of the museum’s cafe. The work is made unassuming in its location within the gallery, and further fails to bear any significant information on its designated tag, besides “Buste d’Africain." (2) These circumstances of encountering the bust are not isolated, there are other busts placed behind the reception desk, and near the ticket counter both of which Jefferson made paintings, and which similarly lack information provided by the museum. (3)

The consistency in the treatment of these busts by the museum is by no means an accident. The provisionality of their placement and lack of information point to the colonial foundations upon which the museum was erected, maintained, and continues to embody. This method of historical erasure, through the negotiation of what information is provided versus what is omitted, is one which acts to uphold and justify the eurocentrism of western art historical record. It is in the colonial agenda of the museum which while in its desire to classify and index art historical archives, willfully decenters and declassifies depictions of non-White bodies – sidelining them to displays adjacent to cafes and ticket counters.

Jefferson is interested in this positionality of encounter, and the subsumed hierarchies therein. In Café Jefferson recreates the image of the bust within the Petit Palais, including the cafe sign, which at its corner overlaps the bust, rivaling the bust in scale. At the forefront of the composition emerges the back of a museum visitor, who turned away from our view, appears to be both viewing the bust and the cafe sign at once. Yet while the architecture of the Petit Palais appears as mist mid-diffusion, the centrality of the composition is rendered in the precise weight and detail given to the bust. The bust comes forward, rendered in a rich umber, made bold against the muted background, which seems at any moment to fall away. The effect made is a visual hierarchy of presence which poses the question of what and how objects are made visible within institutional spaces. Jefferson is engaged in a critique of the institutional spaces of art history, which asks us to think about how museums present objects to us, the spaces they are oriented in and the information given. Jefferson’s paintings are about the position of seeing, and how history is not fixed but is in constant reorientation.

Adrienne Sarasy

Esteban Jefferson’s Café (2020) is part of his recent exhibition Petit Palais, shown at Tanya Leighton, Berlin. The oil on linen work, presents itself in a state of being drafted, washes of muted pink and beige tones melting over blue and graphite colored lines, from which the composition’s forms emerge. There is a sensation of aged parchment rendered within the painting’s surface, bearing the gridded lines of an architectural blueprint or more pointedly, the residual line systems of high renaissance underpainting.

As a whole the composition depicts an encounter Jefferson had with an unattributed bust of an African figure during a visit to the Petit Palais in Paris. (1) Unlike the majority of the works of art in the Petit Palais, which are held in the numerous galleries and bear a tag indicating the works title, maker and provenance, this work is placed obscurely in a foyer next to which is a sign pointing visitors in the direction of the museum’s cafe. The work is made unassuming in its location within the gallery, and further fails to bear any significant information on its designated tag, besides “Buste d’Africain." (2) These circumstances of encountering the bust are not isolated, there are other busts placed behind the reception desk, and near the ticket counter both of which Jefferson made paintings, and which similarly lack information provided by the museum. (3)

The consistency in the treatment of these busts by the museum is by no means an accident. The provisionality of their placement and lack of information point to the colonial foundations upon which the museum was erected, maintained, and continues to embody. This method of historical erasure, through the negotiation of what information is provided versus what is omitted, is one which acts to uphold and justify the eurocentrism of western art historical record. It is in the colonial agenda of the museum which while in its desire to classify and index art historical archives, willfully decenters and declassifies depictions of non-White bodies – sidelining them to displays adjacent to cafes and ticket counters.

Jefferson is interested in this positionality of encounter, and the subsumed hierarchies therein. In Café Jefferson recreates the image of the bust within the Petit Palais, including the cafe sign, which at its corner overlaps the bust, rivaling the bust in scale. At the forefront of the composition emerges the back of a museum visitor, who turned away from our view, appears to be both viewing the bust and the cafe sign at once. Yet while the architecture of the Petit Palais appears as mist mid-diffusion, the centrality of the composition is rendered in the precise weight and detail given to the bust. The bust comes forward, rendered in a rich umber, made bold against the muted background, which seems at any moment to fall away. The effect made is a visual hierarchy of presence which poses the question of what and how objects are made visible within institutional spaces. Jefferson is engaged in a critique of the institutional spaces of art history, which asks us to think about how museums present objects to us, the spaces they are oriented in and the information given. Jefferson’s paintings are about the position of seeing, and how history is not fixed but is in constant reorientation.

- Miki Kanai, “Depicting the “Bizarre” Real World," Talking About Art, December 7, 2020, http://talkingaboutart.de/esteban-jefferson-miki-kanai-tanya-leighton-berlin.

- Precious Adesina, “Esteban Jefferson,” Art In America (May/June 2021), 82. Via Tanya Leighton: https://www.tanyaleighton.com/content/2-artists/11-esteban-jefferson/jefferson_artinamerica_2021.pdf

- Martin Herbert, “Esteban Jefferson, Tanya Leighton," Artforum (March 2021), https://www.tanyaleighton.com/content/2-artists/11-esteban-jefferson/jefferson_artforum_march2021.pdf